Press releases

Why not listen to a book? The Audiolib phenomenon has arrived in France…

Lagardère Publishing

Paris, February 21, 2008

You can now listen to the books everyone is talking about!

Gilles Hertzog interviews Audiolib’s Director Valérie Lévy-Soussan

G.H.: How did the idea for Audiolib come about?

V.L.-S.: It was simply an idea whose time had come.

The growth of the audiobook segment abroad couldn’t be ignored at the Frankfurt Book Fair – giving cause for reflection and leading Hachette, Albin Michel and France Loisirs to wonder how the same phenomenon could be created in France.

Audiobooks have been available in France for a long time. But the phenomenon has not developed on anywhere near the same scale as it has Germany or the UK – not to mention the United States – where audiobooks are given equal billing in bookstores with regular books.

The fundamental idea behind the founding of Audiolib was that when a book is read aloud, it has an extra dimension – the human voice – which brings it to life. The second key idea was to bring out audiobooks at the same time as their release in “book form”. In the countries where audiobooks have the strongest appeal, their audience is drawn to the bestsellers of the moment. We plan to take the same approach in France.

Finally, our audiobooks will physically resemble “real” books: the packaging will have the same format and cover as the book, with a CD of the complete work inside.

The goal is to make the new audiobook a highly accessible product in several different ways: by its price (only one or two euros more than the book version); by that fact that it resembles a book, not a CD; by releasing popular new titles (such as the latest Amélie Nothomb, or the next Harlan Coben); by the ease with which the entire book can be “read” (with the effort of reading out of the way, the listener can immediately concentrate on the pleasure of the words themselves).

G.H.: In concrete terms, how did this project take shape?

V.L.-S.: We studied the audiobook market in the United States, where there are 25,000 titles in bookstores, and in Germany, where there are 15,000 titles, while in France, barely 2,500 titles are available! We were convinced that the solution was to bring together the best authors, an excellent distribution plan and a high level of expertise. And Hachette, Albin Michel and France Loisirs came up with just the right blend of talents. Our energy and the cooperation of a wide variety of publishers should ensure that the market gets going.

G.H.: Why the name Audiolib, instead of Audiolivre?

V.L.-S.: Audiolib is generic in nature, conveying the two-pronged idea of freedom (liberté) and bookstore (librairie), converging on the idea of books (livres). Just consider the name Velib’ (Paris’s new self-service bike system). Proof, if needed, that we’re in sync with the times.

If people start calling audiobooks “Audiolibs”, we can call the brand a real success!

G.H.: What is the reason for this similarity between the Audiolib products and books?

V.L.-S.: One of the keys to success is that audiobooks must remain an integral part of the book world, rather than just another multimedia product. The Audiolib book-shaped case really differs from a simple CD-book. The reaction by the British and Americans was: “You are taking a luxurious approach”. But we are simply playing on the similarity with books, and using the same degree of care in their fabrication.

Our intent is to offer an example, at our own level, of the “famous French cultural exception”. We wanted to spark the interest of the general public, and make it clear that we are part of the bookstore world.

G.H.: The author Christine Angot reads her works in the theatre, while the actor Fabrice Luchini reads on stage with enormous success. Reading festivals such as the Marathon des Mots are drawing ever-larger audiences. In what way does the voice alone transform a text?

V.L.-S.: Behind a voice, there is always a human being. Last year, at the Atelier theatre, Sami Frey read Beckett’s Cap au pire (Worstward Ho in English), seated in the dark. That was the ultimate in physical disembodiment. But the voice was projected by the theatre. In every voice, there is a body. The voice embodies the presence of the actor and, beyond that, the singular presence of the characters. In several of our books, the performer’s talent consists precisely in making us hear and in giving substance to a whole cast of characters, solely through the modulations of the voice, its rhythm and intonation.

G.H.: The voice with its inflections, modulations and music, adds another dimension to the literal meaning of the text. Through its dramatic own drama, it also touches the emotions. Is the spoken word more forceful than a silently read text?

V.L.-S.: Any text has several layers of meaning. Our goal is not to add another layer, but to give those that are already there a chance to be heard. There are highly interpretive ways of reading. We chose a more “neutral” style, to leave the mind free and give the imagination a chance to work. When a text is embodied by the voice alone, the most important thing is the music of the words, the rhythm of the phrasing. The listener has the unique privilege of being able to adopt the author’s style, and focus his or her entire attention on the story that is being told!

G.H.: Reading is a solitary activity. With an audiobook, the listener is captivated by the voice, its inflections, its phrasing, its drama and so on…

V.L.-S.: This embodiment of a text by the spoken word stimulates the imagination. Any narrative is a form of seduction. There is also a child-like dimension. When we were children, we were told stories that we still remember. It is this dimension that an audiobook re-activates: a concern for our well-being by a friendly voice, offering us a moment of pure escape.

G.H.: What else does the listener gain?

V.L.-S.: I liked Mal de pierres by the Italian author Milena Agus, an extremely musical book.

We said to ourselves: “That’s a story that should be heard aloud”. When the narrator, Sandrine Willems, read it aloud, each sentence took on a new dimension. The entire text revealed a musical undercurrent. We will want to rediscover any book that we really enjoyed reading by listening to it. And vice versa.

G.H.: You say that listening to a text reminds us of our childhood.

Does this memory effect make the listener a child of the text?

V.L.-S.: From birth on, our awakening to life is achieved to a great extent through our mother’s voice. We are indelibly marked by this primal relationship. Her voice assures us that we are not alone in the world. Woody Allen’s Radio Days shows how an entire family is held together thanks to the radio: the voices heard on the radio represent an opening up to the world, even if it is an imaginary world. In a similar manner, several people can listen to an audiobook, and share the pleasure of listening together, in the car or at home with their families. You can put on earphones, insert the audiobook into a computer, or play it on a hi-fi system. In Germany, the whole family listens to audiobooks together. The audio book fosters both personal and collective intimacy.

As for the problem of getting young people to read, I can still see myself in the car with my 14-year-old son, listening to Luchini read Un coeur simple (A simple heart) by Flaubert. When we got home, my son put the CD on his stereo system. He was any amazed when his teacher talked about the book a few days later and his reaction was: “Isn’t that the story I listened to? I didn’t know that I was reading Flaubert”.

G.H.: As a matter of fact, Flaubert tried out his sentences by reciting them aloud as soon as he had written them. He called the study in which he declaimed his texts his “gueuloir” (his “shouting room”). Dumas and Kafka read their manuscripts to their friends. Do you think that Audiolib can influence certain authors to structure their books as spoken texts? Could this new media engender a new way of writing?

V.L.-S.: Even if writers do not necessarily read their works aloud, they still hear the work’s rhythm, phrasing and melodies in their heads. In the books we select, the phrasing always has a musical dimension. From the very outset, the voice is central to writing.

Through Audiolib, a number of writers have rediscovered the pleasure of reading their works aloud. Marc Levy, for example, wanted to recount the genesis of his book to the actors himself and comment on certain passages, and even read the most moving parts.

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt plays each of his characters differently, like a true man of the theatre. And Sylvie Testud offers a marvellous interpretation of Amélie Nothomb’s ironic sensibility. Jacques Salomé puts himself into each of his works with a great deal of tenderness. Philippe Grimbert told us that he discovered a whole new dimension of Un secret when he read it himself for Audiolib. The very simple sentences fit his voice perfectly. Flaubert practiced this technique exhaustively, so that everything – from the least comma to the manner of linking consonants – would sound perfect to the ear.

G.H.: For the launch of Audiolib, you selected twelve titles with wide appeal. For future releases, do you plan to consider scholarly works – from the social sciences for example, such as Lévi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques – or philosophy, or perhaps even correspondence between authors?

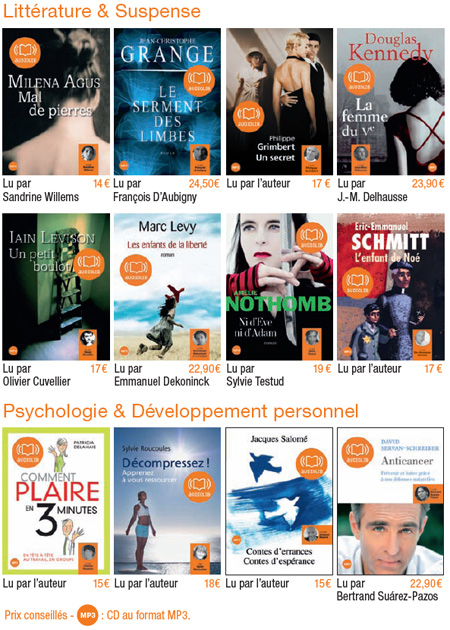

V.L.-S.: We would like to move towards the social sciences and less well-known works, to introduce them to a new audience. But the audience must be there first. Many current audiobooks already draw on the classical repertoire, which is no longer copyright protected, but that approach is not going to increase the popularity of this market. To create a general ripple effect, Audiolib will propose works by contemporary authors that have already won the attention of a wide audience as soon as the “regular” edition is released. We are beginning with Milena Agus, Jean-Christophe Grangé, Douglas Kennedy, Marc Levy, Amélie Nothomb, David Servan-Schreiber, as well as Patricia Delahaie, Philippe Grimbert, Jacques Salomé, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt, who read their books themselves.

We can consider Audiolib a success when people start thinking in bookstores: “I like this author and would really like to hear this work read; I’m sure that would give me just as much pleasure as reading it – and maybe even more”.

40 TITLES SCHEDULED FOR RELEASE IN 2008:

- The first 12 titles will be launched on 13 February 2008.

- Additional publications will be released in March and April 2008 (François Cheng, Philippe Claudel, Harlan Coben, Henri Loevenbruck etc.…)

Communications agency:

Valerie Solvit - Tel.:+33 (0)1 42 61 24 63 - solvitcom@wanadoo.fr

Email alert

To receive institutional press releases from the Lagardère group, please complete the following fields:

Register